I was staring at a packet capture, trying to figure out why my script wasn't receiving audio data.

The device was clearly working. LED on. App showing audio levels. But when I subscribed to the audio characteristic—the standard approach for every BLE audio device I'd ever worked with—nothing came through.

So, I opened Wireshark as usual and examined the raw packets.

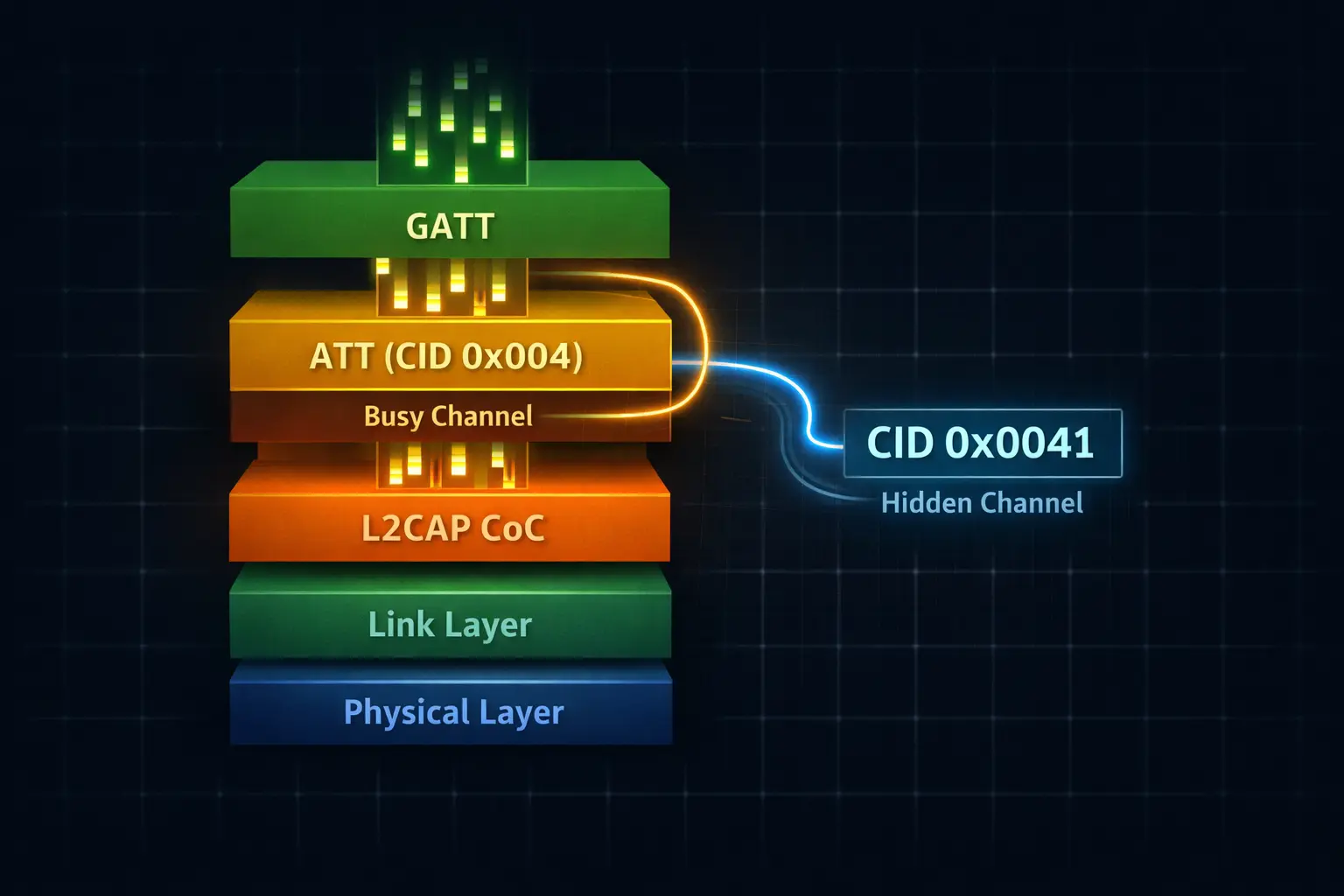

The GATT traffic appeared normal. There was service discovery, characteristic reads, and control commands being exchanged. Then, I noticed something unusual: audio-sized packets were moving through a channel I didn't recognize.

CID 0x0041. That's not GATT.

GATT runs on CID 0x0004, a fixed channel for the ATT protocol. What I was looking at was a dynamic channel, an L2CAP Connection-Oriented Channel.

I'd read about this in the Bluetooth spec sometime ago and promptly forgotten about it, because I'd never seen it used in the real world.

Someone was actually doing it differently.

How Bluetooth LE Actually Works

Before I explain why this matters, let me walk you through how BLE moves data. If you've worked with BLE before, you probably interact with GATT: services, characteristics, notifications. But GATT is just the top layer of a stack, and understanding the layers below it explains why there's a better way.

The Stack

┌─────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Application │ ← Your code

├─────────────────────────────────────┤

│ GATT (Generic Attribute) │ ← Services & characteristics

├─────────────────────────────────────┤

│ ATT (Attribute Protocol) │ ← Read/write/notify operations

├─────────────────────────────────────┤

│ L2CAP │ ← Packet framing & channels

├─────────────────────────────────────┤

│ Link Layer │ ← Radio packets

├─────────────────────────────────────┤

│ Physical Layer │ ← 2.4 GHz radio

└─────────────────────────────────────┘

Physical Layer: The actual radio, broadcasting at 2.4 GHz.

Link Layer: Handles the raw radio packets. This is where Bluetooth defines how devices advertise, connect, and exchange data over the air. The original BLE spec (4.0) limited each packet to 27 bytes of payload. Bluetooth 4.2 introduced Data Length Extension (DLE), allowing up to 251 bytes.

L2CAP (Logical Link Control and Adaptation Protocol): Think of this as the postal service. It takes data from higher layers, adds a 4-byte header with length and channel ID, and hands it to the Link Layer. It can also segment large messages across multiple packets and reassemble them on the other side.

ATT (Attribute Protocol): Defines a simple database of "attributes"—small pieces of data identified by handles (like memory addresses). ATT provides operations to read, write, and get notifications about these attributes.

GATT (Generic Attribute Profile): Builds on ATT to create a hierarchical structure. Attributes are grouped into "characteristics" (a value plus metadata), which are grouped into "services" (a collection of related characteristics). This is the layer most developers interact with.

How Data Flows in GATT

When your fitness tracker sends your heart rate to your phone, here's what happens:

Your phone discovers the Heart Rate Service (UUID

0x180D)Inside that service, it finds the Heart Rate Measurement characteristic

Your phone enables notifications by writing to a special descriptor (CCCD)

The tracker sends notifications whenever your heart rate changes

Each notification travels: GATT → ATT → L2CAP → Link Layer → Radio → Phone

The key point is that GATT and ATT always operate on a fixed L2CAP channel (CID 0x0004). Every service, characteristic, and notification is sent through this single channel.

This works great for small, infrequent data like heart rate or temperature readings. It gets awkward for streams.

The Problem with GATT for Streaming

Let's do the math on what happens when you push audio through GATT.

Packet Size Constraints

The Link Layer defines how much data fits in a single over-the-air packet:

| BLE Version | Link Layer Payload | L2CAP Header | Available for ATT |

| 4.0 / 4.1 | 27 bytes | 4 bytes | 23 bytes |

| 4.2+ (DLE) | 251 bytes | 4 bytes | 247 bytes |

That 23-byte or 247-byte figure is your ATT_MTU, the maximum size of an ATT operation.

But wait, there's more overhead. A GATT notification needs:

1 byte for the ATT opcode (notification =

0x1B)2 bytes for the attribute handle

So your actual payload per notification is ATT_MTU minus 3:

| Scenario | ATT_MTU | Notification Payload |

| Default (no DLE) | 23 bytes | 20 bytes |

| With DLE | 247 bytes | 244 bytes |

What This Means for Audio

Say you're streaming 16-bit audio at 16 kHz mono. That's 32 KB per second of raw PCM data.

Without DLE (20-byte notifications):

32,000 ÷ 20 = 1,600 notifications per second

Each notification has 7 bytes of overhead (L2CAP + ATT headers)

You're sending 11,200 bytes of overhead per second just in headers

With DLE (244-byte notifications):

32,000 ÷ 244 = ~131 notifications per second

Much more reasonable, but still constrained

Most devices use compressed audio (Opus, AAC) at lower bitrates, so the math isn't quite this brutal. But the fundamental problem remains.

The Bigger Problem: No Flow Control

Here's what really hurts: GATT notifications are fire-and-forget.

The server sends a notification. The client either receives it or doesn't. There's no acknowledgment, no backpressure, no way for the client to say "slow down, I'm busy."

If the client's Bluetooth stack gets temporarily overwhelmed due to a CPU spike, garbage collection, or another app using Bluetooth, packets can just vanish. The server keeps sending without realizing, and your audio experiences glitches.

For a heart rate notification every second, this rarely matters. For 131 audio packets per second, it's a real problem.

The Alternative: L2CAP Connection-Oriented Channels

Remember that L2CAP layer sitting below ATT? It turns out you can use it directly, bypassing GATT entirely.

L2CAP Connection-Oriented Channels (CoC) were added in Bluetooth 4.1. Instead of shoving everything through the fixed ATT channel, you open a dedicated channel for your data stream.

How It Works

Central (Phone) Peripheral (Device)

│ │

│══ LE Credit Based Connection ═══════►│

│ PSM: 0x0080 │

│ MTU: 2048 │

│ MPS: 247 │

│ Initial Credits: 10 │

│ │

│◄═════ Connection Response ═══════════│

│ Assigned CID: 0x0041 │

│ Credits: 10 │

│ │

│◄══════════ Data ════════════════════ │

│◄══════════ Data ════════════════════ │

│◄══════════ Data ════════════════════ │

│ │

│═══════ More Credits ═══════════════► │

│ (flow control) │

│ │

Let me break down the terminology:

PSM (Protocol/Service Multiplexer): Like a port number in TCP. Identifies what protocol or service this channel is for. Values 0x0001–0x007F are reserved by the Bluetooth SIG. Values 0x0080–0x00FF are for custom applications.

CID (Channel Identifier): A unique ID for this specific channel on this specific connection. Dynamic channels use CIDs from 0x0040 to 0x007F.

MTU (Maximum Transmission Unit): The largest "message" (SDU: Service Data Unit) you can send. The spec allows up to 65,535 bytes, though memory constraints usually limit this to a few KB.

MPS (Maximum PDU Size): The largest single packet (PDU: Protocol Data Unit) on this channel. L2CAP will automatically segment larger SDUs into MPS-sized chunks.

Credits: Here's the magic. Each credit allows the sender to transmit one PDU. When you run out of credits, you stop sending. The receiver grants more credits when it's ready for more data.

Credit-Based Flow Control

This is the key difference from GATT.

Initial state:

Device has 10 credits from Phone

Device sends audio packet #1 → Credits remaining: 9

Device sends audio packet #2 → Credits remaining: 8

Device sends audio packet #3 → Credits remaining: 7

...

Device sends audio packet #10 → Credits remaining: 0

Device must wait...

Phone finishes processing, sends 8 more credits

Device receives credits → Credits available: 8

Device resumes sending

If the phone's app is busy, it doesn't grant more credits. The device waits instead of flooding packets into the void. When the phone catches up, it grants credits and data flows again.

No dropped packets. No glitches from buffer overflow. The sender always knows the receiver is ready.

Side-by-Side Comparison

Let me put the two approaches next to each other:

GATT Notification (with DLE)

┌─────────────────┬────────────┬──────────────────────┐

│ L2CAP Header │ ATT Header │ Payload │

│ (4 bytes) │ (3 bytes) │ (up to 244 bytes) │

└─────────────────┴────────────┴──────────────────────┘

Channel: Fixed (CID 0x0004)

Max payload: 244 bytes per notification

Max characteristic value: 512 bytes total

Flow control: None

Discovery required: Yes (services, characteristics, CCCD)

L2CAP CoC K-frame (with DLE)

┌─────────────────┬──────────────────────────────────┐

│ L2CAP Header │ Payload │

│ (4 bytes) │ (up to 247 bytes) │

└─────────────────┴──────────────────────────────────┘

(First frame of SDU includes 2-byte SDU length field)

Channel: Dynamic (CID 0x0040–0x007F)

Max payload: 247 bytes per PDU, up to 65,535 bytes per SDU

Flow control: Credit-based

Discovery required: No (just need to know the PSM)

The per-packet efficiency is similar, both are around 97% payload. The wins for CoC are:

Flow control prevents data loss under load

Larger logical units (64KB SDU vs 512-byte characteristic)

No GATT overhead (service discovery, handles, CCCDs)

Symmetric bidirectional (both sides equally efficient)

The Ecosystem Gap

When I tried to work with L2CAP CoC from my usual tools, I ran into a wall.

# bleak - the standard Python BLE library

# L2CAP CoC support: None

# GitHub issue #598: closed as wontfix

Bleak is a GATT client. It doesn't expose L2CAP directly, and the maintainers have decided that's outside scope.

The pattern repeats across cross-platform tools:

| Platform / Library | GATT | L2CAP CoC |

| iOS (CoreBluetooth) | ✅ | ✅ (since iOS 11) |

| Android | ✅ | ✅ (since API 29) |

| Web Bluetooth | ✅ | ❌ |

| Python (bleak) | ✅ | ❌ |

| Flutter (flutter_blue_plus) | ✅ | ❌ |

| React Native (ble-plx) | ✅ | Native modules only |

The native SDKs support it. The cross-platform libraries don't. If you're building with Flutter or React Native; which many teams choose for faster iteration, you'd need to drop into Swift and Kotlin separately.

That's not a dealbreaker for everyone, but it explains why most tutorials, Stack Overflow answers, and sample code stick to GATT.

The Documentation Gap

Search "BLE GATT tutorial" and you'll find hundreds of results. Nordic, TI, Espressif, Silicon Labs—every chip vendor publishes getting-started guides with working sample projects.

Search "BLE L2CAP CoC tutorial" and you get the Bluetooth Core Specification and a handful of sparse API references.

When I needed to understand the credit-based flow control details, I ended up reading the spec. It's not that the information doesn't exist, it's that nobody has packaged it into the kind of step-by-step guides that make GATT feel approachable.

When CoC Makes Sense

Despite the tooling gap, L2CAP CoC is worth considering for specific use cases:

Streaming where reliability matters: If dropped packets mean audible glitches or corrupted data, credit-based flow control prevents the silent failures that GATT notifications allow.

Bulk transfers: Firmware updates, file sync, log downloads. The 512-byte characteristic limit in GATT requires chunking logic. CoC can send larger SDUs natively.

Controlled ecosystems: If you build both the firmware and the app—and don't need third-party integrations—the compatibility concerns shrink. You're writing native code anyway.

Bidirectional real-time data: Control systems where both directions need equal efficiency and guaranteed delivery.

A clean architecture separates concerns:

GATT (control plane)

├── Device configuration

├── Status queries

├── PSM advertisement

└── Standard services (Device Info, Battery)

L2CAP CoC (data plane)

├── Audio streaming

├── File transfer

└── High-frequency sensor data

Use the database for database things. Use the pipe for pipe things.

LE Audio Changes the Equation

Bluetooth LE Audio is now shipping on recent devices; AirPods Pro (2nd gen), iPhone 14 and later, Samsung Galaxy S23 series, Pixel 7 and up. The LC3 codec and isochronous channels provide a standardized path for audio streaming that's built into the spec.

For new products targeting current hardware, LE Audio is the right answer. It handles the codec, the transport, and the synchronization. You don't need to roll your own.

But LE Audio requires Bluetooth 5.2+ hardware on both ends. The installed base of older devices—phones from 2020, fitness trackers, smart home gadgets—won't get LE Audio support through software updates. That tail is long.

If you're building for the current generation, use LE Audio. If you need to support older devices, or you're working on something LE Audio doesn't cover (non-audio bulk data, custom protocols), L2CAP CoC remains the better-than-GATT option that most developers don't know exists.

Quick Reference

Key Numbers

| Parameter | Default (BLE 4.0/4.1) | With DLE (BLE 4.2+) |

| Link Layer payload | 27 bytes | 251 bytes |

| L2CAP header | 4 bytes | 4 bytes |

| ATT_MTU | 23 bytes | 247 bytes (optimal) |

| GATT notification payload | 20 bytes | 244 bytes |

| Max characteristic value | 512 bytes | 512 bytes |

| L2CAP CoC SDU max | 65,535 bytes | 65,535 bytes |

Platform Support

| Platform | GATT | L2CAP CoC | Since |

| iOS (CoreBluetooth) | ✅ | ✅ | iOS 11 (2017) |

| Android | ✅ | ✅ | API 29 (2019) |

| Web Bluetooth | ✅ | ❌ | — |

| Python (bleak) | ✅ | ❌ | — |

| Flutter | ✅ | ⚠️ Native only | — |

| React Native | ✅ | ⚠️ Native only | — |

L2CAP CoC Terminology

| Term | Meaning |

| PSM | Protocol/Service Multiplexer - like a port number |

| CID | Channel Identifier - unique ID for this channel |

| MTU | Maximum SDU size (logical message) |

| MPS | Maximum PDU size (single packet) |

| SDU | Service Data Unit - your actual data |

| PDU | Protocol Data Unit - one L2CAP packet |

| Credits | Flow control tokens - one credit = one PDU allowed |